Cancer precursor project - characteristics of premalignant precursors, part 3a (dermatopathology)

6 May 2024, revised 17 May 2024

Our Cancer precursor project is intended to better understand how cancer arises by compiling a regularly updated spreadsheet of all distinct human cancers (now 1,230) and their precursors (now 185).

In part 1, we noted that the percentage of identified precursors varies widely by pathology subspecialty (see table below) and we discussed precursors for subspecialties with epithelial sites (breast, head & neck, gyn, GI/liver, GU/adrenal and thoracic).

Epithelial malignancies typically have known risk factors associated with chronic inflammation (microorganisms, parasites, autoantigens, trauma, excess weight, diet, aging), DNA changes (carcinogen exposure, germline changes, radiation, aging), constitutive hormone production (estrogens, androgens, insulin) or immune system dysfunction (Pernick 2021). These risk factors promote changes in molecular pathways that produce intraepithelial neoplasia or dysplasia, in situ carcinoma and ultimately invasive malignancies.

In part 2, we discussed neuropathology related malignancies and their lack of precursors and speculated that contrary to current thinking, most nonepithelial malignancies may lack precursors. These nonepithelial malignancies often have no known risk factors and may arise from random processes or “bad luck” (Pernick 2022).

In the skin, of the 79 distinctive malignancies identified to date, only 6 malignancies have known precursors (5 melanocytic, 1 nonmelanocytic):

Invasive melanoma: precursor is dysplastic nevus

Superficial spreading melanoma (low CSD [cumulative sun damage] melanoma): precursor is also dysplastic nevus

Lentigo maligna melanoma: precursor is lentigo maligna

Acral melanoma: precursors are acral lentiginous melanoma in situ and acral nevus

Melanoma arising in giant congenital nevus: precursor is giant congenital nevus

Squamous cell carcinoma: precursors are actinic keratosis / keratinocytic dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma in situ

These 6 malignancies with known precursors are either epithelial (squamous cell carcinoma) or reside within an epithelium (melanoma). Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is derived from squamous epithelial cells. Melanoma derives from melanocytes, which are not epithelial but reside in a network of epithelial keratinocytes that, we believe, constrains their malignant transformation in a similar manner as epithelial cells.

Melanocytes are dendritic-like cells that derive from the neural crest. Melanocytes produce not only melanin but neurotransmitters and other hormones, making them part of the skin’s neuroendocrine network (Chen 2022). In the skin, they are present in its deepest layer (stratum basale), surrounded by keratinocytes.

Keratinocytes are highly specialized epithelial cells in the skin (Eckert 1989) that surround the melanocytes with a ratio of 10 keratinocytes to one melanocyte in 2 dimensions (Dodia 2023). Melanocytes have dendrites that allow them to contact up to 40 keratinocytes over long distances in the skin (Domingues 2020).

We speculate that within the skin, the cell - cell connections of squamous epithelial cells or keratinocytes and their basement membranes may force some of these malignancies to go through a premalignant, intraepithelial neoplasia process because the cell - cell connections make inappropriate cell division more difficult and the basement membrane limits invasion unless additional DNA changes are present.

In this essay, we discuss the first 3 dermatologic malignancies with known precursors:

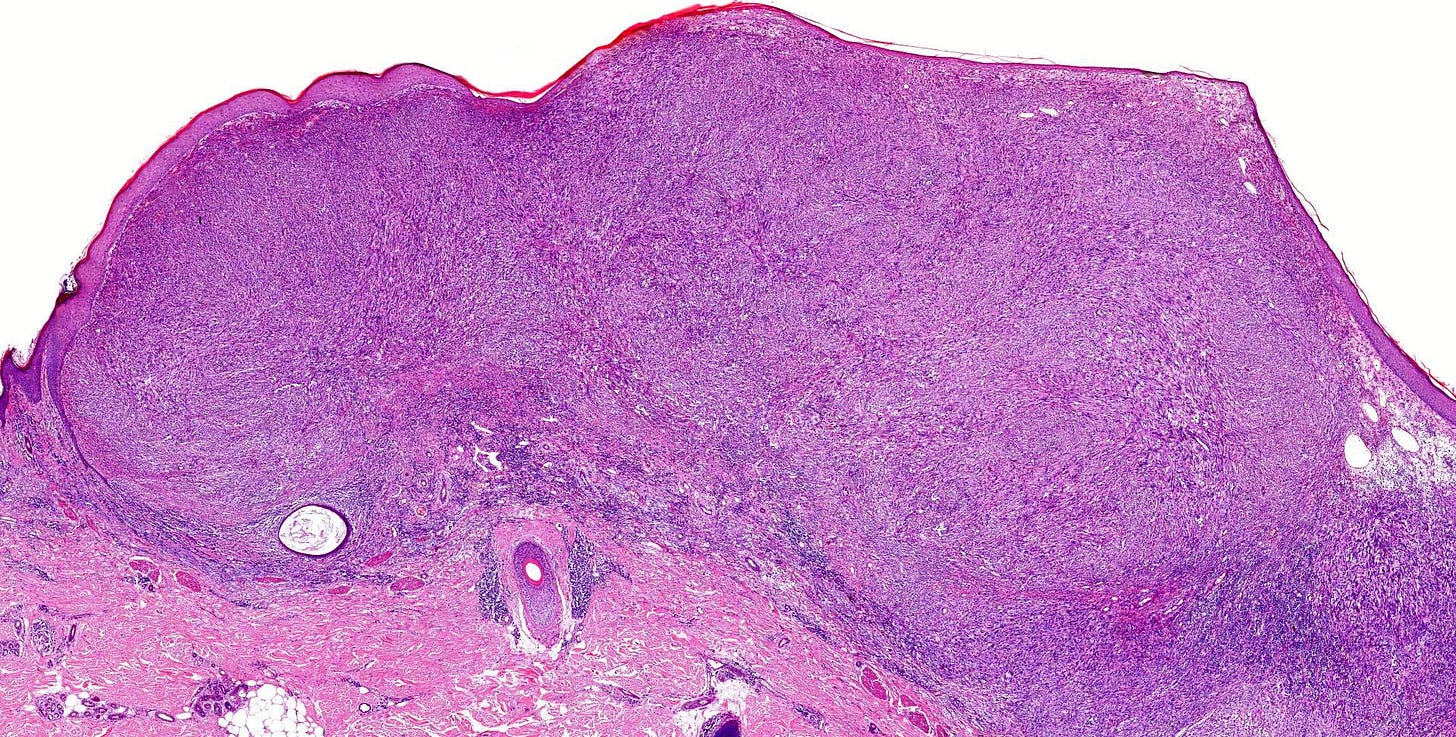

1 & 2. Dysplastic nevus is a precursor of invasive melanoma and superficial spreading melanoma (low CSD melanoma) but it is a controversial topic (Drozdowski 2023).

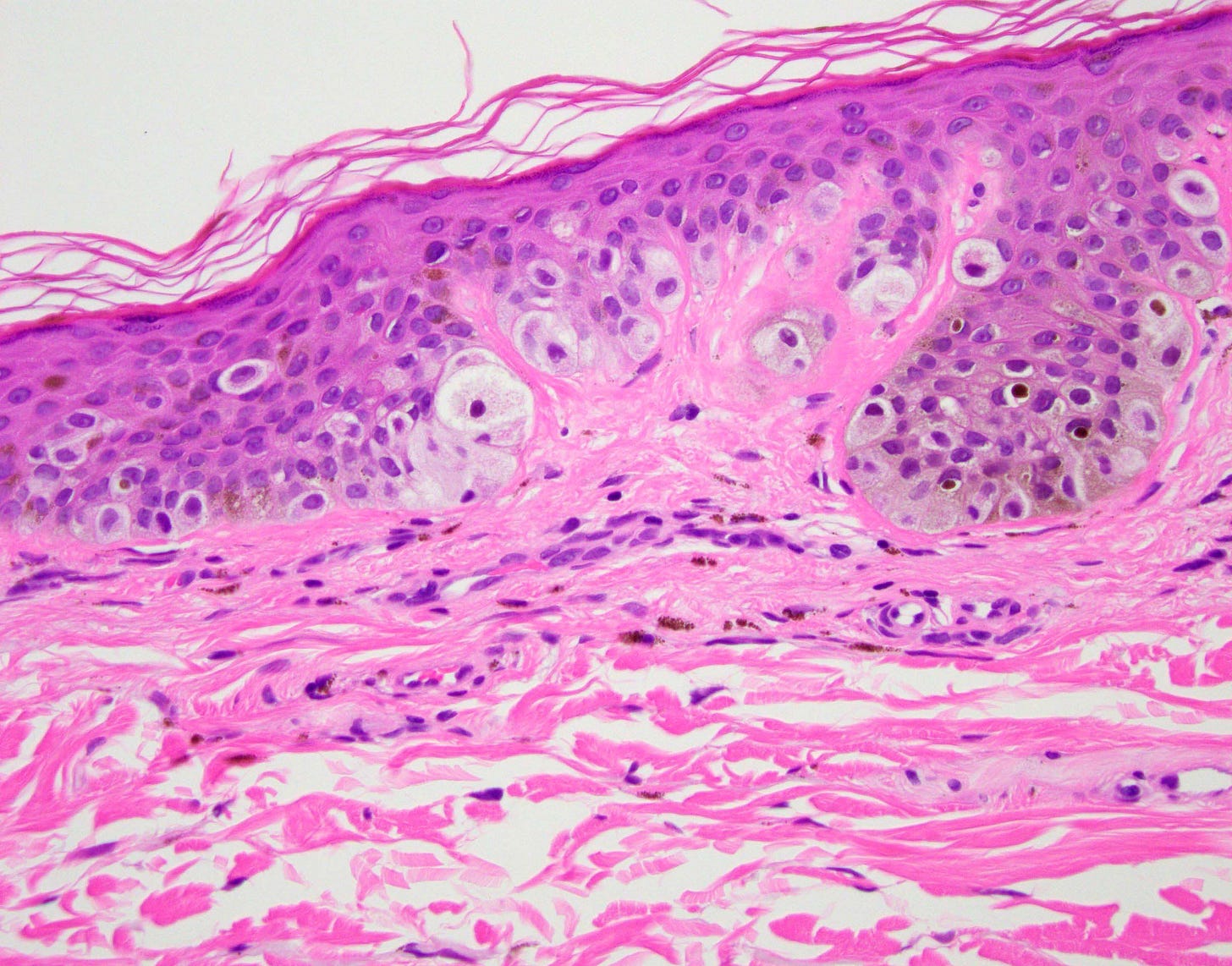

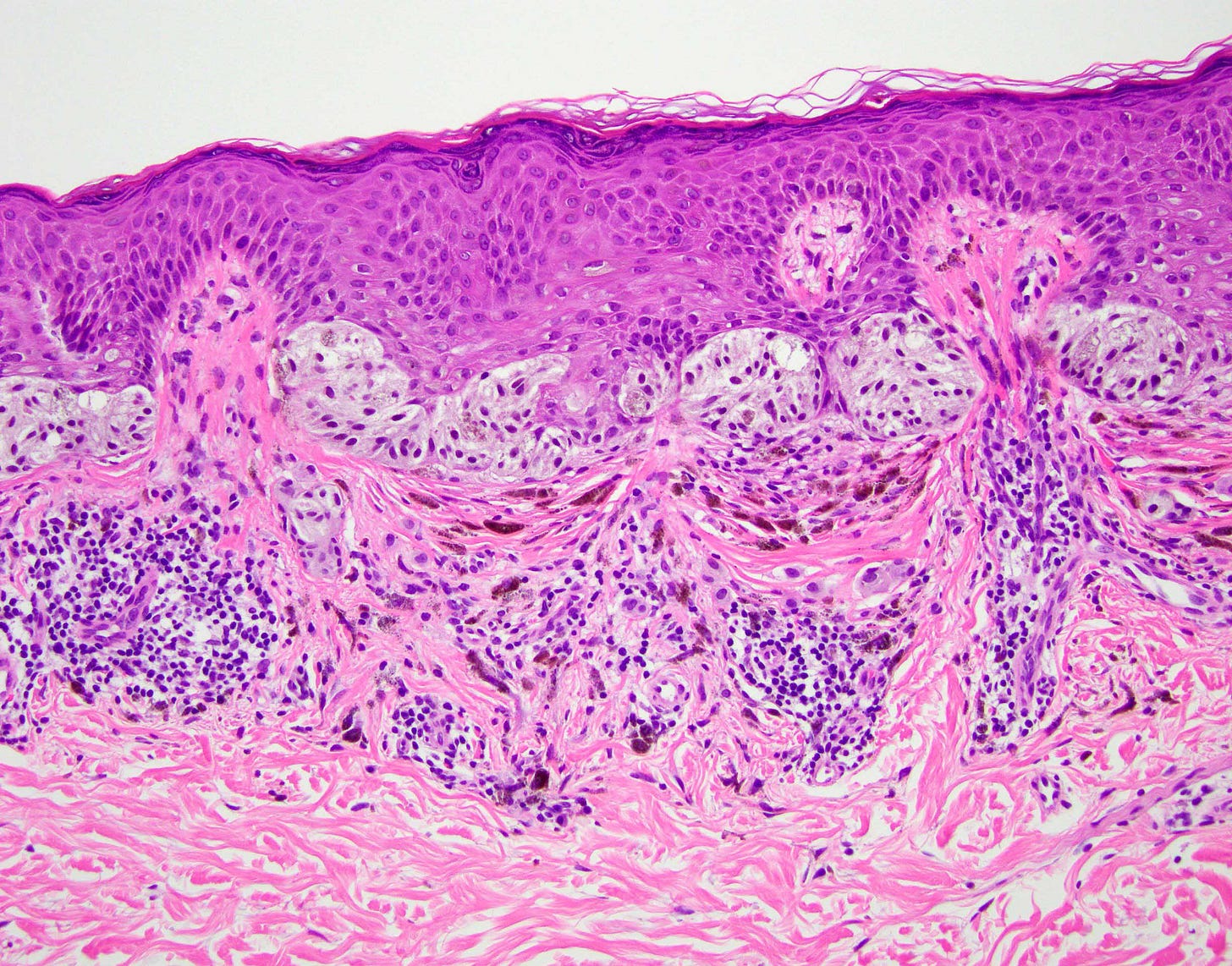

Dysplastic nevus

Dysplastic nevi are pigmented lesions that share the clinical and histological features of common nevi and melanoma. Most never progress to melanoma. Although many melanomas arise without a detectable precursor lesion, 25% are associated with a melanocytic nevus (Martín-Gorgojo 2018), which may or may not be dysplastic (Cymerman 2016). The progression from dysplastic nevus to melanoma is not well understood (Asadbeigi 2023). Patients whose nevi have more severe atypia (Arumi-Uria 2003) or who have family members with melanoma (Silva 2011) have a higher risk for melanoma. The risk of melanoma increases as the number of dysplastic nevi increases (Bhatt 2016). Patients with familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (familial dysplastic nevus syndrome) have an increased risk of developing other malignancies, particularly pancreatic cancer (Vasen 2000).

The two types of melanoma (invasive melanoma and superficial spreading melanoma) associated with dysplastic nevi are described below:

Invasive melanoma

Superficial spreading melanoma

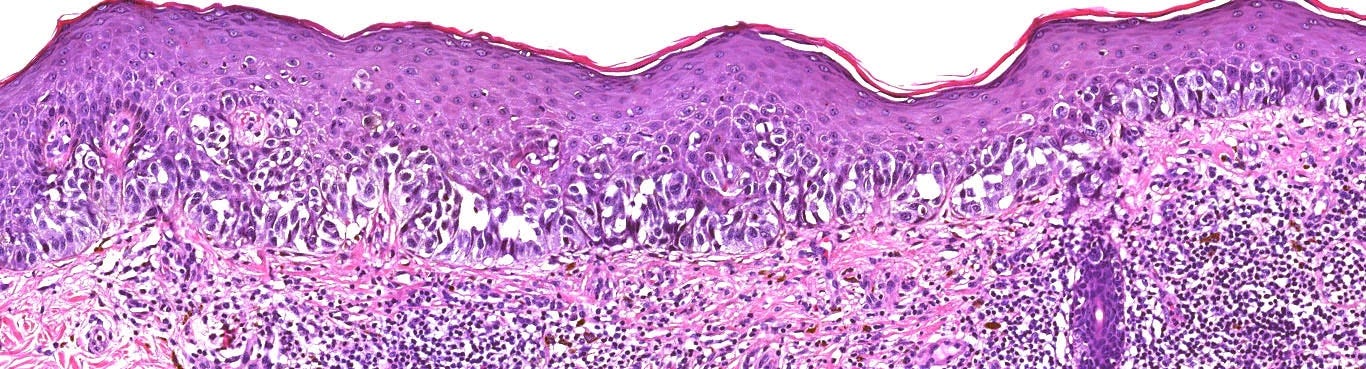

3. Lentigo maligna is a precursor of lentigo maligna melanoma.

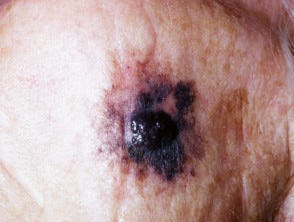

Lentigo maligna

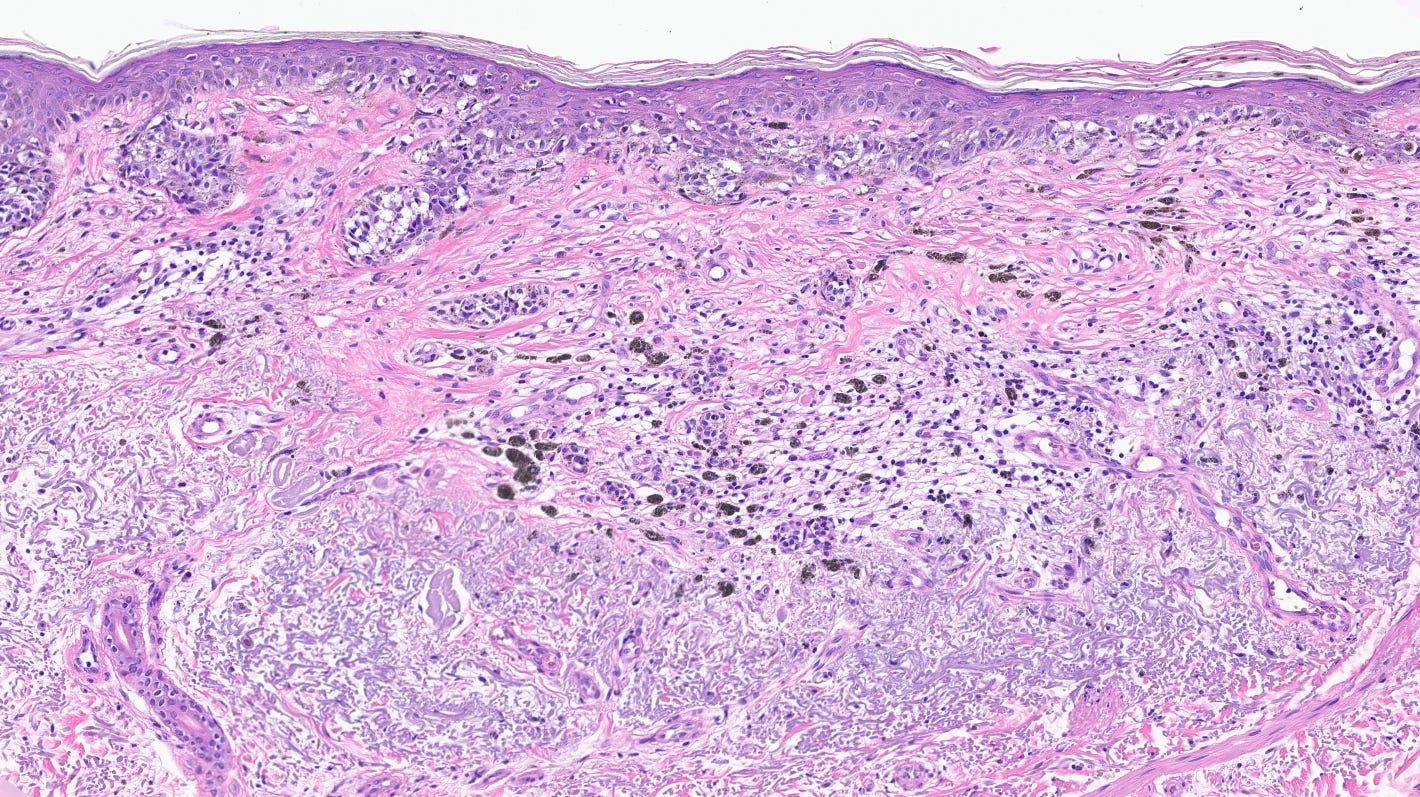

Lentigo maligna refers to the in situ (precursor) form of this disease, while lentigo maligna melanoma designates invasive disease. The precursor arises on the chronic sun damaged skin of patients on the face, neck, ears, scalp not covered by hair, forearms and dorsal hands of patients 50+ years. It presents as an irregularly pigmented macule, corresponding to an intraepidermal proliferation of atypical melanocytes.

Lentigo maligna appears to arise due to the acquisition of genetic mutations by chronic ultraviolet light exposure (Bastian 2014).

Lentigo malignant melanoma

In part 3b, we will discuss the last 3 dermatologic malignancies with known precursor lesions.

If you like these essays, please subscribe or share them with others. These essays will continue to be free. Instead of giving me money, please repost these essays and strive to make our world a better place and yourself a better person.

Click here for the Index to Nat’s blog on Cancer and Medicine

Follow us on Substack, LinkedIn, Threads and Instagram (npernickmich) and Tribel (@nat385440b).

Follow our Curing Cancer Network through our Curing Cancer Newsletter, on LinkedIn or Twitter or the CCN section of our PathologyOutlines.com blog. Each week we post interesting cancer related images of malignancies with diagnoses plus articles of interest. Please also read our CCN essays.

Latest versions of our cancer related documents:

American Code Against Cancer (how you can prevent cancer)

Email me at Nat@PathologyOutlines.com - Unfortunately, I cannot provide medical advice.

I also publish Notes at https://substack.com/note. Subscribers will automatically see my Notes.

Thanks for this interesting summarizing piece. However, there are two issues that I believe need some adjustments. First, melanomas are not epithelial in origin. They arise from neuroectodermal cells and exhibit a different immunophenotype.

Secondly, the concept of dysplastic nevi is still controversial. Many, in fact at least 2/3of all melanomas arise de novo, i.e. without clinically evident precursor lesions; conversely, most clinically atypical nevi whose majority by inference will show histologic „dysplasia“ never turn into a melanoma. Acute UV exposure alone is sufficient to induce histologic „dysplasia“ in common nevi which illustrates the poor positive predictive value of dysplastic histologic features. Lastly, the criteria for differentiating severe melanocytic „dysplasia“ from early/thin melanoma are at least partially subjective. The illustrations above are a case in point: in the high magnification picture that is labeled „dysplastic nevus“ I personally would diagnose an established malignant melanoma.

There is also enlightening study regarding the association between melanocytic nevi and melanoma by Martin-Gorgojo et al. from 2018.